Photo by Eric Preston

Status/Protection

- Global Rank: G5 Key to global and state ranks

- State Rank: S1B

- WBCI Priority: SGCN, State Endangered

Population Information

The Federal BBS information can be obtained at http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/bbs.html by clicking on Trend Estimates and selecting the species in question. All estimates are for time period (1966-2005).

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey: non-significant increase

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (WI): N/A

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 23): N/A

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 12): N/A

- WSO Checklist Project: stable (1983-2007)

Life History

- Breeding Range: Scattered localities across North America (McNicholl et al. 2001)

- Breeding Habitat: Emergent Marsh, Southern Sedge Meadow and Marsh.

- Nest: Ground or floating nest within clumps of vegetation near open water (McNicholl et al. 2001).

- Nesting Dates: Eggs: Late May to mid-July (Robbins 1991).

- Foraging: High dives, aerial forage (Ehrlich et al. 1988).

- Migrant Status: Short-distance migrant, Neotropical migrant.

- Habitat use during Migration: Fresh, brackish, and salt water marshes (McNicholl et al. 2001).

- Arrival Dates: Mid-April to early June (Robbins 1991).

- Departure Dates: Early August to mid-October (Robbins 1991).

- Winter Range: Florida to Texas and the Caribbean (McNicholl et al. 2001).

- Winter Habitat: Similar to habitat used during migration.

Habitat Selection

The Forster’s Tern nests in a wide variety of wetland habitats including fresh, brackish, and saltwater marshes, lake islands consisting of submerged land or emergent vegetation, marshy borders of lakes and streams, and extensive deep- or shallow-water inland marshes (Mossman 1988, McNicholl et al. 2001). Nest sites in Wisconsin are most often in large marshes or wetland complexes containing large stands of thin to moderately thick emergent vegetation, such as cattail, bulrush, phragmites, arrowhead, and/or bur-reed (Mossman 1988). Nests are commonly within close proximity to open water and are placed on muskrat houses (Bergman et al. 1970, McNicholl et al. 2001), rooted cattail bases, floating vegetation mats (Cuthbert and Louis 1993), dredge spoil islands, and artificial nesting platforms (Techlow and Linde 1983, Mossman 1988). The Forster’s Tern often nests in the same marshes as Black Terns but select larger substrates elevated higher above the water. Thus, the two species do not appear to compete for nest sites (Bergman et al. 1970). The Forster’s Tern generally nests in colonies ranging from several pairs to hundreds of pairs, but solitary nests also occur (McNicholl et al. 2001). Colony sites shift from year to year depending upon water levels and availability of suitable habitat (Robbins 1991).

Habitat Availability

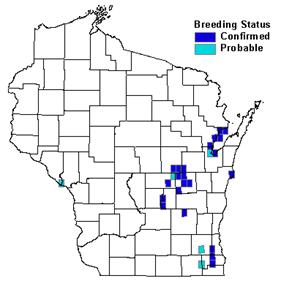

Historically, the Forster’s Tern nested at Lake Koshkonong (Jefferson County), Pewaukee Lake (Waukesha County), Lake Puckaway (Green Lake County), Big Muskego Lake (Waukesha County), and Horicon Marsh (Dodge County). The highest concentrations of nesting Forster’s Terns now occur in the area containing Lakes Poygan, Winneconne, and Butte des Morts (Winnebago County) (Mossman 1988, Matteson 2006). Several of the historically important nesting sites (e.g., Lake Koshkonong, Pewaukee Lake) no longer harbor breeding colonies, possibly due to unsuitable habitat conditions. Artificially high water levels maintained by man-made dams, carp activity that prevents the establishment of aquatic vegetation, lakeshore development, (Mossman 1988) and the spread of invasive plant species impact the quality of colony sites (WDNR 2005). The impacts of habitat degradation at colony sites are compounded by the irreparable loss of wetland complexes in the state. Prior to Euro-American settlement, wetlands occupied an estimated four million hectares of the total fourteen million hectares of Wisconsin’s land area. Today, 53%, or 2.1 million hectares, of these wetland habitats remain (WDNR 1995). Strict wetland use regulations and incentive programs designed to restore or enhance wetlands, such as the Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program and Wetland Reserve Program, have helped to curb habitat loss and protect existing wetlands (WDNR 1995). Furthermore, artificial nest platforms have provided alternative nest sites and improved nest success considerably in some areas (Techlow and Linde 1983).

Population Concerns

In the late nineteenth century, the Forster’s Tern was considered a common summer resident in the Green Bay area and inland lakes throughout the state (Kumlien 1891). Nesting colonies have disappeared or declined since that time and the Forster’s Tern breeding population has experienced marked instability in the state, primarily due to the lack of suitable nesting habitat (Pritzl 2006). By the mid-twentieth century, the Forster’s Tern was considered a rare summer resident and breeder (Barger et al. 1942, cited in Pritzl 2006) and was listed as a Wisconsin endangered species in 1979. Mossman (1988) proposed a recovery goal of 800 pairs at ten or more colonies with no more than half of all nests on artificial structures. Recent statewide surveys indicate that these goals have not yet been met. During the last two breeding seasons, Wisconsin has supported more than 400 breeding pairs at five colony sites: Lake Poygan, Lake Puckaway, Horicon Marsh, Rush Lake, and Big Lake Muskego (Matteson 2006). The primary factor limiting populations appears to be the availability of high-quality nest sites that are free of mammalian and avian predators and not subject to water level fluctuations.

Recommended Management

The restoration of large marsh and wetland complexes and the prevention of further wetland loss should be management priorities for this species. High priority restoration sites include Rush Lake, Green Bay west shore, Winnebago Pool Lakes (including Lake Poygan), Horicon Marsh Wildlife Area, and Big Muskego Lake (WDNR 2005). Land acquisition, conservation easements, and enforcement of existing wetland protection regulations also will improve the status of wetland ecosystems in the state (Hands et al. 1989). Partnerships between the WDNR and organizations dedicated to wetland conservation are essential to the long-term management and conservation of wetland complexes that provide breeding habitat for this species (WDNR 2005). At traditional colony sites, managers should avoid using pesticides to prevent reduction and contamination of food sources (Hands et al. 1989) and stabilize water levels during the breeding season. In areas where water levels cannot be managed, installing artificial nesting platforms may provide a secure nest site. Wherever feasible, managers should consider restricting access near colony sites to eliminate or reduce adverse effects of human disturbance. Finally, managers should develop and implement education programs to engage local communities in Forster’s Tern conservation.

Research Needs

Mossman (1988) suggested several research needs for Wisconsin: (1) conduct statewide survey to determine breeding population, number of colonies, production of young, and causes of reproduction failures and mortality at colonies; (2) identify sites to receive artificial nest platforms and dredge spoil deposits; (3) conduct comparative studies of reproductive rates at natural and artificial sites; (4) determine the effects of ongoing habitat management on colonies; (5) determine wintering and migration areas of Wisconsin’s Forster’s Tern; and 6) continue monitoring of contaminants in the Great Lakes. The winter ecology of the Forester’s Tern also needs more study (McNicholl et al.2001).

Information Sources

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology species account: http://www.birds.cornell.edu/AllAboutBirds/BirdGuide/Forsters_Tern.html

- North American Breeding Bird Survey: http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/bbs.html

- Tern colony site management techniques: http://www.waterbirdconservation.org/plan/rpt-sitemanagement.pdf

- Waterbird Conservation for the Americas: http://www.waterbirdconservation.org/pubs/ContinentalPlan.cfm

- Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas: http://www.uwgb.edu/birds/wbba/

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources fact sheet: http://www.dnr.state.wi.us/org/land/er/factsheets/birds/Fortern.htm

References

- Barger, N.R., E.E. Bussewitz, E.L. Loyster, S.D. Robbins, and W.E. Scott. 1942. Wisconsin birds – a preliminary checklist with migration charts. Wisconsin Society for Ornithology, Madison, WI.

- Bent, A.C. 1963. Life histories of North America gulls and tern. Dover Publications, Inc. New York.

- Bergman, R.D., P. Swain, and M.W. Weller. 1970. A comparative study of nesting Forster’s and Black terns. Wilson Bulletin 82:435-444.

- Brown, M., and J.J. Dinsmore. 1986. Implications of marsh size and isolation for marsh bird management. Journal of Wildlife Management. 50:397-397.

- Cuthbert, F.J. and M.Y. Louis. 1993. The Forster’s Tern in Minnesota: status, distribution, and reproductive success. Wilson Bulletin 105(1): 184-187. Fevold, B.M. 1998. The 1997 breeding population study of Forster’s and Black terns at Horicon National Wildlife Refuge. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Report.

- Hands, H.M., R.D. Drobney, and M.R. Ryan. 1989. Status of the Black Tern in the northcentral U.S. Report to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 15pp.

- Kumlien L. 1891. List of the birds known to nest within the boundaries of Wisconsin, with a few notes thereon. Wisconsin Naturalist 1: 103-105, 181-183.

- Matteson, S.W. 2006. Conservation of endangered, threatened and nongame birds. Performance Report, 1 July 2005-30 June 2006. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison.

- McNicholl, M.K., P.E. Lowther, and J.A. Hall. 2001. Forester’s Tern (Sterna forsteri). In A. Poole and F. Gill, eds. The birds of North America, No 595. The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, and the American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington D.C.

- Mossman, M.J. 1988. Wisconsin Forster’s Tern recovery plan. Endangered Resource Report 42. Bureau of Endangered Resources, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. 102 pp.

- Pritzl, J. 2006. Forster’s Tern. In Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Wisconsin (N.J. Cutright, B.R Harriman, and R.W Howe, eds.). Wisconsin Society of Ornithology, Inc. 602pp.

- Robbins, S. D. 1991. Wisconsin birdlife: population & distribution, past & present. Univ of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI.

- Scharf, W.C. 1979. Nesting and migration areas of birds of the U.S. Great Lakes (30 April to 25 August 1976). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of Biological Services. FWS/OBS-77/2. 113 pp.

- Techlow, A.F. III, and A.F. Linde. 1983. Forster’s Tern nest platform study for 1983. Wisconsin Endangered Resources Report 7. Bureau of Endangered Resources, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison. 16 pp.

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR). 2005. Wisconsin’s Strategy for Wildlife Species of Greatest Conservation Need. Madison, WI.

Contact Information

- Compiler: Dan Haskell, danhaskell@hotmail.com

- Editor: Kim Kreitinger, K.Kreitinger@gmail.com