Status/Protection

- Global Rank: G5 Key to global and state ranks

- State Rank: S4B

- WBCI Priority: SGCN, PIF, State Special Concern

Population Information

The Federal BBS information can be obtained at http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/bbs.html by clicking on Trend Estimates and selecting the species in question. All estimates are for time period (1966-2005).

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey: significant decline

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (WI): significant decline

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 23): non-significant decline

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 12): significant decline

- WSO Checklist Project: stable (1983-2007)

Life History

- Breeding Range: Throughout eastern U.S. west to the Great Plains; local breeding populations in western states (Vickery 1996).

- Breeding Habitat: Dry Prairie, Dry-mesic Prairie, Hay, Pasture, Fallow Field, Idle Cool-season Grasses, Idle Warm-season Grasses, Pine Barrens, Sand Barrens, Oak Opening.

- Nest: Ground.

- Nesting Dates: late May-July.

- Foraging: Ground glean.

- Migrant Status: Short distance.

- Habitat use during Migration: grasslands and native prairies.

- Arrival Dates: late April.

- Departure Dates: September.

- Winter Range: Southern U.S., Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean.

- Winter Habitat: grasslands and native prairie.

Habitat Selection

Found in open grasslands and prairies (Vickery 1996) such as fallow fields, pastures, idle short to medium height grasslands, dry old fields, and open barrens. This species is especially abundant in larger tracts of native dry prairie (Sample and Mossman 1997). Some bare soil is required and stiff-stemmed forbs are attractive song perches. Most common in relatively short vegetation with areas of bare ground and clumps of taller dense vegetation. Can inhabit taller grass habitats if vegetation is patchy and not overly dense (Sample and Mossman 1997). Grasshopper Sparrows prefer larger tracts of habitat (Vickery 1996) and are at least moderately area-sensitive (DeChant et al. 2003, Herkert et al. 1993).

Habitat Availability

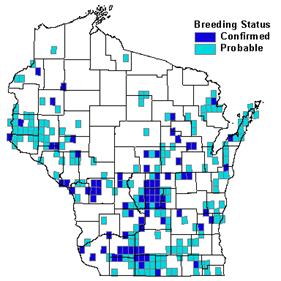

This species is still commonly found on larger tracts of dry grassland or pasture in many parts of the state, but has undergone substantial declines. Native prairie currently covers 1% of the landscape in the southern half of Wisconsin, the majority in public ownership, however; most of the population of this species probably resides on non-native grassland types on private lands. This is a species that has suffered greatly from the intensification of agricultural efforts as it used to be abundant in hay fields, fallow fields and pastures.

The bulk of the Grasshopper Sparrow population is located in the Southwest Savanna and Central Sand Hills ecological landscapes. Land set aside in the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) has contributed to surrogate grassland habitat where many species of grassland birds have shown positive responses to these designated fields (Reynolds et al. 1994, Johnson and Igl 1995). In addition, state properties such as the Greenwood Wildlife Area that have restored dry grasslands also provide critical habitat. In general, much of the existing grasslands are vulnerable to mowing in the middle of the breeding season or lost completely to cultivation. Frequent mowing, intensive grazing, change in agricultural practices, expanding urbanization, and the invasion of non-native woody vegetation, grasses, and forbs have greatly reduced the quality of grassland habitat available to many grassland birds, including Grasshopper Sparrows (Rich et al 2004).

Population Concerns

Grasshopper Sparrows have shown some of the most alarming and persistent declines of any breeding bird in Wisconsin since the advent of the Federal Breeding Bird Survey. Despite wide-spread loss of prairie, Grasshopper Sparrows adapted well to pasture and hay systems before they became too intense to support grassland birds. The Grasshopper Sparrow population has declined nationwide 69% since the 1960’s. Their reproductive rate is also notably low with no clear answer as to why (Vickery 1996), but literature supports the fact that ground nesting grassland birds tend to be more susceptible to predation events at the nest (Wiens 1968, Vickery et al 1992, and Martin 1993). Grasshopper Sparrows also seem to be less common where savannah sparrows are abundant (Robbins 1991). Wiens (1973) found that Grasshopper Sparrow established a different portion of the habitat continuum than Savannah Sparrows possibly to alleviate competitive pressures. However, Grasshopper Sparrows have shown favorable responses to areas that have been managed to improve the habitat (Vickery 1996). Grasshopper Sparrows still respond well to management and restoration of dry grasslands in Wisconsin, but current land use trends and agricultural practices will probably continue to cause population declines on unmanaged areas.

Recommended Management

Management for this species should seek to create the short-grass, low-litter layer conditions that are associated with this species’ presence in an open, grass-dominated landscape. In Illinois, patches of grass >10-30 ha were needed to support this species (DeChant et al. 2003). This can be done by restoring native dry prairies on appropriate sites or by managing non-native grassland types (hay, pasture, fallow field) within a larger bird conservation area framework. On larger sites, seek to maintain a mosaic of grassland successional stages (treat 20-30% of total area annually) throughout the treatment area (DeChant et al. 2003).

Site-level management can incorporate burning, mowing, grazing or other disturbance systems as necessary to create the proper structure for this species. Delayed mowing, especially on public lands and airports, light to moderate grazing, and burning may be beneficial for Grasshopper Sparrows (Vickery 1996). Avoid treating areas during the nesting season; mowing or intensive grazing should be delayed until after July 15 (Sample and Mossman 1997). The use of fire and light grazing can be used in alternating lots of grasslands to achieve a more heterogeneous vegetation structure that could benefit grassland birds that use a diverse continuum of vegetation structure (Rich et al 2004). Grasshopper Sparrows will remain in fields cut during the breeding season to renest, however their reproductive success in these second attempts is unknown. They will also colonize a field not long after it has been burned and will tolerate moderate grazing for the diverse vegetation structure and bare areas these practices create. Contour strip cropping, an agricultural practice in southwestern Wisconsin, is also an effective compromise between row crop production and bird conservation for attracting Grasshopper Sparrows (Sample and Mossman 1997). The use of native grasses and forbs in CRP plantings could benefit Grasshopper Sparrows by offering diversity in vegetation structure (Rich et al 2004). Most old, un-managed smooth brome fields are not suitable habitat for this species and should be periodically rejuvenated through disturbance.

Research Needs

No data has been collected on winter mortality to determine if winter survivorship is a problem. More detailed understanding of why reproductive success appears to be low and use productivity data to determine how to manage habitats that will yield greater reproductive success (Vickery 1996).

Information Sources

- Effects of Management on Grassland Birds: Grasshopper Sparrow

- North American Breeding Bird Survey: http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov

- David Sample, Grassland Community Ecologist, Wisconsin DNR Research Center, 1350 Femrite Dr., Monona, WI 53716.

- Wisconsin Breeding Bird Atlas: http://www.uwgb.edu/birds/wbba/

- Temple S. A., J. R. Cary, and R. Rolley. 1997. Wisconsin Birds; A Seasonal and Geographical Guide. Wisconsin Society of Ornithology and Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison, WI.

References

- Dechant, J. A., M. L. Sondreal, D. H. Johnson, L. D. Igl, C. M. Goldade, M. P. Nenneman, and B. R. Euliss. 2003. Effects of management practices on grassland birds: Grasshopper Sparrow. Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, Jamestown, ND. Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center Online. http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/literatr/grasbird/grsp/grsp.htm (Version 12AUG2004).

- Herkert, James R., Robert E Szafoni, Vernon M. Kleen, and John E. Schwegman.1993. Habitat establishment, enhancement and management for forest and grassland birds in Illinois. Division of Natural Heritage, Illinois Department of Conservation, Natural Heritage Technical Publication #1, Springfield, Illinois. Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center Online. http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/birds/manbook/manbook.htm (Version 16JUL97).

- Johnson, D.H., and L. D. Igl. 1995. Contributions of the Conservation Reserve Program to populations of breeding birds in North Dakota. Wilson Bulletin 107: 709-718.

- Knutson, M. G., G. Butcher, J. Fitzgerald, and J. Shieldcastle. 2001. Partners in Flight Bird Conservation Plan for The Upper Great Lakes Plain (Physiographic Area 16). USGS Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center in cooperation with Partners in Flight. La Crosse, WI.

- Martin, T. E. 1993. Nest predation among vegetation layers and habitat types: revising the dogmas. American Naturalist 141: 897-913.

- Reynolds, R.E., T. L. Shaffer, J.R. Sauer, and B.B. Peterjohn. 1994. Conservation Reserve Program: benefit for grassland birds in the northern plains. Transactions of the North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference 59: 328-336.

- Rich, T.D., C.J. Beardmore, H. Berlanga, P.J. Blancher, M.S. W. Bradstreet, G.S. Butcher, D.W. Demarest, E.H. Dunn, W.C. Hunter, E. E. Inigo-Elia, J.A. Kennedy, A. M. Martell, A. O. Panjabi, D. N. Pashley, K. V.Rosenberg, C. M. Rustay, J. S. Wendt, T.C. Will. 2004. Partners in Flight North American Landbird Conservation Plan. Cornell Lab of Ornitholgy. Ithaca, NY.

- Robbins, S. D., Jr. 1991. Wisconsin Birdlife: Population and distribution past and present. Madison, WI: Univ. Wisconsin Press.

- Sample, D. and M. Mossman. 1997. Managing Habitat for Grassland Birds: A Guide for Wisconsin. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources: Madison, WI.

- Vickery, P.D. 1992. A regional Analysis of Endangered, Threatened, and Special Concern Birds in the Northeastern United States. Transactions of the Northeast Section of the Wildlife Society 48: 1-10.

- Vickery, P.D.1996. Grasshopper Sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum). In the Birds of North America, No. 239 (A. Poole and F. Gill eds.). The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, PA and The American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, DC.

- Wiens, J. A., 1968. An Approach to the Study of Ecological Relationships among Grassland Birds. Ornithological Monographs. 8: 1-93.

- Wiens, J.A., 1973. Interterritorial habitat variation in Grasshopper Sparrow and Savannah Sparrow. Ecology, Vol.54. No. 4

Contact Info

- Compiler: Jenny Herrmann

- Editor: Susan M. Vos comments submitted by Richard Henderson