Status/Protection

- Global Rank: G5 Key to global and state ranks

- State Rank: S3S4B

- WBCI Priority: SGCN, State Threatened

Population Information

The Federal BBS information can be obtained at http://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/bbs.html by clicking on Trend Estimates and selecting the species in question. All estimates are for time period (1966-2005).

*Note: There are important deficiencies with these data. These results may be compromised by small sample size, low relative abundance on survey route, imprecise trends, and/or missing data. Caution should be used when evaluating this trend.

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey: significant increase

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (WI): significant increase*

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 23): significant increase*

- Federal Breeding Bird Survey (BCR 12): significant increase*

- WSO Checklist Project: significant increase (1983-2007)

- DNR Eagle/Osprey Survey: Stable. About 400 pairs statewide in the past 8 years.

Life History

- Breeding Range: Alaska south to California and east across Canada and the Great Lakes states to the Atlantic Coast (Poole et al. 2002).

- Breeding Habitat: Inland Open Water.

- Nest: Platform: large stick nests on snag or man-made structure. About 75% of nests in Wisconsin are on artificial platforms.

- Nesting Dates: Late April or early May.

- Foraging: High dives.

- Migrant Status: Neotropical Migrant.

- Habitat use during Migration: Few data; broad diverse habitat.

- Arrival Dates: March 15.

- Departure Dates: Mid-August - October.

- Winter Range: Central and South America.

- Winter Habitat: Large shallow, fresh water inland lakes and coastal waters.

Habitat Selection

Poole et al. (2002) lists some common features of nesting habitat including an adequate supply of accessible fish within 10-20 km from the nest; shallow waters (0.5-2 m deep), which generally provide accessible fish; and open, elevated nest sites usually over or near water. Nest trees are usually tall, with flat or dead tops. Dead-topped pines (Pinus spp.) are the preferred nest trees in Wisconsin (Eckstein 1999). In recent years, Ospreys in Wisconsin have used man made towers and poles as nest sites including transmission line poles, cell phone towers, light poles, and fire towers (R. Eckstein, pers. comm.). The large nest (1-2 m diameter; 3-4 m deep) is constructed of sticks (2-4 cm diameter; 1 m in length) and lined with grasses, mosses and various other materials (Bent 1961, Poole et al. 2002).

Houghton and Rymon (1997) summarized the distribution and abundance of the U.S. Osprey population in the 48 states. Their survey of state and federal agencies found about 10,000 pairs nesting from Maine to Florida to Texas along the Atlantic Coast and Gulf of Mexico. Another 3,000 pairs nested throughout the western states. The Great Lakes states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan supported about 1,000 pairs. Eckstein et al. (2004) reported the Wisconsin population to be 405 nesting pairs in 2003.

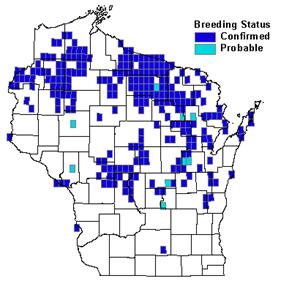

Before European settlement, Osprey nested throughout Wisconsin near major lakes and rivers, however, their were no historical records for the muddy Mississippi River or the Apostle Islands (Kumlien and Hollister 1903). Today, Osprey breeding pairs are concentrated in the inland lakes regions of north central and northwestern Wisconsin and along the Wisconsin River and its reservoirs in central Wisconsin (Eckstein et al. 2004). Ospreys prefer to nest and forage in the shallow waters of the state’s many large reservoirs. In 2003 the top four counties with breeding pairs include Oneida (82), Sawyer (28), Washburn (27), and Vilas (25).

Habitat Availability

Wisconsin ’s Osprey habitat includes inland lakes; the large reservoirs found in northern and central Wisconsin; large river systems such as the Flambeau, Chippewa, Wisconsin, and Wolf; and the reservoirs found on many commercial cranberry bogs and wildlife management areas. It is not known whether Lake Superior, the Apostle Islands, and Lake Michigan are suitable breeding habitat. In 2003, Ospreys occupied less than half of the available statewide habitat (Eckstein et al. 2004). The statewide Osprey population is concentrated in northern and central Wisconsin with few nesting pairs in western, east central, and southern Wisconsin.

A very successful Osprey nest platform program by WDNR was active in Wisconsin between 1972 and 1993 (Eckstein 1999). In recent years, electric power and transmission line companies have erected many platforms to secure Osprey nests on transmission highlines. In 2003 over 75% of all Ospreys nested on various artificial platforms and structures in Wisconsin. Suitable nest natural nest sites may be limiting the distribution and abundance of Ospreys in Wisconsin (R. Eckstein, pers. comm.).

Population Concerns

Osprey population declines were evident by the early 1900s due to egg collecting, predation, harvesting of large trees for timber and indisciminant shooting (Bent 1961, Poole et al. 2002). Populations in Wisconsin and throughout the U.S. began to decline dramatically in the 1950s due to the use of organochlorine pesticides (Poole et al. 2002). In Wisconsin, Sindelar (1971) reported an annual decline of 19% per year from 1965-1969. In 1972, the Osprey was placed on the state’s list of endangered species. The use of organochlorine pesticides (particularly DDT/DDE) after World War II resulted in the thin-shelled egg syndrome that reduced Osprey productivity (Poole et al. 2002). In 1969 DDT was banned in Wisconsin and soon nation wide. The combination of the banning of DDT, protecting nest sites, and securing nests with platforms has helped the Osprey population increase from 82 pairs in 1974 to 405 pairs in 2003 (Eckstein et al. 2004). However, the statewide population has not expanded since 1995. Competion for food and nest sites by bald eagles (Quamen and Naugle 2001), contaminants (Woodford et al. 1998), raccoon predation (Poole1989), human disturbance during nesting, and lack of nest sites in suitable habitat may be limiting the expansion of Wisconsin’s Osprey population. The use of organochlorine pesticides and indiscriminant shooting are still prevalent on the wintering grounds in Central and South America.

Recommended Management

Wisconsin has a long history of protecting and managing the state’s Osprey population. At the core of the management effort is the 31-year Osprey distribution and abundance database. Key to conservation is the annual aerial survey to locate nest sites. Once nest sites are known, wildlife managers can protect them by providing information to private landowners and public land managers. In addition, nests can be secured with platforms and predator guards. Platforms appear to be important because in recent years few Ospreys choose to nest on trees. Wildlife managers need to work closely with Wisconsin’s electric power industry because power transmission lines have become important nest sites for Ospreys.

There is abundant suitable habitat for Ospreys in the extensive Lake Winnebago System and in the inland lake areas of southern and southeastern Wisconsin. Reintroducing the Osprey population to these habitats through hacking could be accomplished by conservation organizations.

Research Needs

The most important research need is to determine why the statewide Osprey population has not increased or expanded since 1995. Studies are needed to determine the dynamics of select local breeding populations, especially changes in the adult breeding cohort. There is a need to understand why Ospreys are declining where they were formally abundant on the Flambeau, Willow, and Rainbow Reservoirs. There is a need to determine why Osprey nestlings are dying late in the nesting season on certain reservoirs. The impact of the expanding Bald Eagle population on the distribution and abundance of Ospreys in the dense inland lakes region needs further analysis (Quamen and Naugle 2001). In addition, we need to learn why Ospreys rely so heavily on man made platforms and do not nest in areas with abundant forage but few man made structures. All research depends on access to and continuation of the long term statewide Osprey nest database.

Information Sources

References

- Bent, A.C. 1961. Life histories of North American birds of prey. Vol. 1. Dover Publications, Inc. New York.

- Eckstein, R. 1999. The Osprey in Wisconsin. The Passenger Pigeon. 61(3): 271-276.

- Eckstein, R., Dahl, B. Ishmael, J. Nelson, P. Manthey, M. Meyer, S. Stubenvoll, and L. Tesky. 2004. Wisconsin Bald Eagle and Osprey Surveys 2003. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Madison. 9 pp.

- Houghton, L.M. and L.M. Rymon. 1997. Nesting distribution and population status of U. S. Ospreys 1994. J. Raptor Res. 31(1): 44-53.

- Kumlien, L. and N. Hollister. 1903. The birds of Wisconsin. Bulletin of the Wisconsin Natural History Society 3 1-143; reprinted with A.W. Schorger’s revisions, Wisconsin Society for Ornithology. 1951.

- Quamen, F.R., and D.E. Naugle. 2001. What’s responsible for the decline in Osprey productivity in northern Wisconsin? M.S. thesis, University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point. 21 pp.

- Poole , A.F. 1989. Ospreys A Natural and Unnatural History. Cambridge University Press. New York. 246 pp.

- Poole , A.F., R.O. Bierregaard, and M.S. Martell. 2002. Osprey (Pandion haliaetus). In The Birds of North America, No. 683 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America , Inc. Philadelphia, PA.

- Robbins, Jr., S.D. 1991. Wisconsin Birdlife, Population and Distribution, Past and Present. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison. 702pp.

- Sindelar, Jr., C.R. 1971. Wisconsin Osprey Survey. Report of the WSO Research Committee. The Passenger Pigeon 33: 79-88.

- Woodford, J.E. 1996. Effects of organochlorine contaminants and other factors on the reproduction rates of Osprey in Wisconsin. M.S. thesis. University of Wisconsin-Madison. 72 pp.

- Woodford, J.E., W.H. Karasov, M.W. Meyer, and L. Chambers. 1998. Impact of 2,3,7,8-TCDD exposure on survival, growth, and behavior of Ospreys breeding in Wisconsin, USA. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 17: 1323-1331.

Contact Info

- Compiler: Dan Haskell, danhaskell@hotmail.com

- Editor: Ron Eckstein, Ronald.Eckstein@Wisconsin.gov